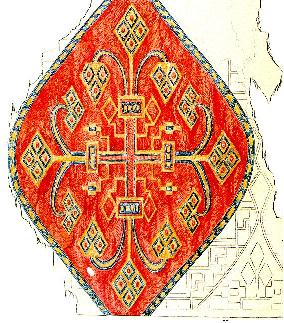

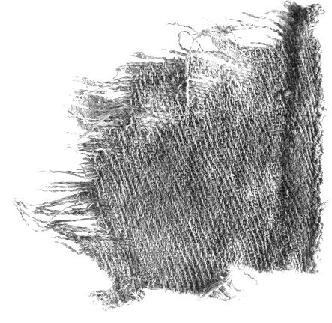

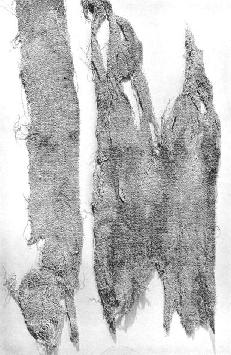

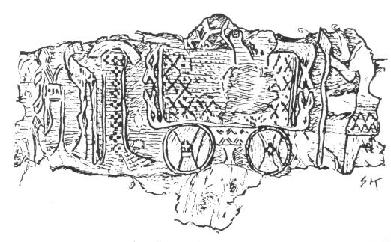

Amongst many other discoveries the Oseberg grave chamber also contained the largest and most varied collection of textiles and textile tools that has ever been found in a single grave. It is without equal in Nordic Prehistory. The collection consists of a number of fragmented tapestries and other patternwoven blankets of wool and linen, tablet woven braids and a large collection of cloth fragments, which come from clothing, sails or tents, rugs and so on, and in addition remains of silk fabrics and silk embroideries. [Picture shows embroidery on woolen cloth. Much enlarged]

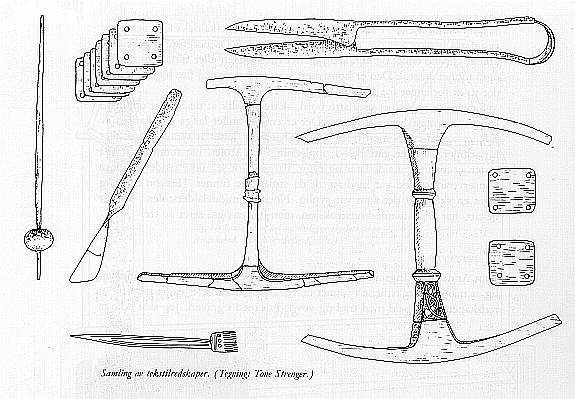

Of textile tools were found several smaller looms, of which one appears to have been a tubular loom and two others were braid looms. There were also a number of small square tablets for tabletweaving, see ill. p. 132.

[Illustration page 132. Collection of textile tools. Drawing by Tone Strenger]

Of spinning tools were found whorls with and without attached spindles and

several loose spindles. A pair of carved wooden pieces may possibly also

have been used during spinning to attach the wool to. There were also a couple

of linen clubs and also a pair of iron shears, which were probably used to

shear the wool off the

sheep.

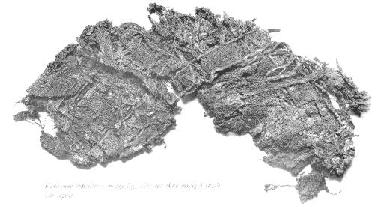

The whole textile material makes up 277 catalog numbers, and when each number can comprise of one to close to a hundred fragments, it shows how extensive this collection is. Some of the textiles are in very bad condition and are now stiff cakes, often in several layers on top of each other. Others are surprisingly well preserved, so fresh and bright it is hard to understand that they've spent over 1000 years in the ground.

The most interesting textiles in the collection are doubtless the tapestries. Professor Bjørn Hougen has already scientifically treated these. His work with the tapestries has been preliminarily published in Viking and is in manuscript form for the fourth volume of the great work on the Oseberg find.

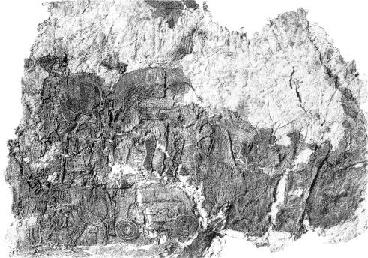

Hougen starts his article in Viking in this manner: "Tapestries and wood carving - in these two words are the starting point for the new perspectives that the Oseberg find has opened for the arts history of the viking age. We are here presented for the first and so far only time with a full selection of forms of artistry that we knew existed, but could not picture, because we lacked practically any actual materials." Such as the tapestry fragments appear today, it is hard to get any real impression of them. Many are so stiff and unclear that any attempt to analyse them is practically impossible.

[Cake of textiles in many layers. It was not possible to separate them all.]

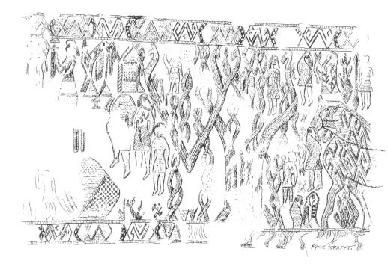

It has been possible to get something from some of them. It turns out that

they have been surprisingly narrow, between 16 and 23 cm wide. The length

can't be determined; but since it must be considered fairly certain that

they were created on the little tubular

loom of which pieces

were found both in the chamber and in the fore, they may, based on the distance

between the cross pieces, have been between 1 m and 1.5 m long. Even though

they are that narrow, these strips are still filled with a diverse richness

of topic, ordered in horizontal rows above each other. As Bjørn Hougen

has suggested, this could have been a primitive attempt at perspective.

of which pieces

were found both in the chamber and in the fore, they may, based on the distance

between the cross pieces, have been between 1 m and 1.5 m long. Even though

they are that narrow, these strips are still filled with a diverse richness

of topic, ordered in horizontal rows above each other. As Bjørn Hougen

has suggested, this could have been a primitive attempt at perspective.

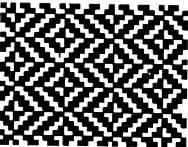

First some words on the technical weaving aspect of these extraordinary tapestries. The warp, which is of wool, has on average ten threads per centimetre. The threads, which make up the figures, are also of wool, but between the individual figures the warpthreads are left exposed. It is unthinkable that this was originally the case. Therefore we must believe there was a double weft system, one of wool which made up the motifs, and one of linen which is now gone. This is known as brocade. The actual brocading is done in twenty different weaving patterns, of which several have an exquisite decorative effect. The outlines of each figure was marked by a thread of a different colour than the background, and it's wound around each warp thread - so called slyngesmett.

Brocading is a special type of weaving technique with ornamentation of differently coloured wool yarn in different weaves and patterns. The warp can be of wool or linen and the background of linen. This kind of fabric is found already in the 7th century in some Swedish graves (Valsgärde. 8 and Valsgärde 6), and in two graves in the Swedish Viking merchant town Birka at Lake Mälaren. In Norway there are fragments of this technique in three Norwegian finds, from Haugen in Rolvsøy, Østfold and Bo in Torvastad, Rogaland and Jåtten in Helland, Rogaland, but above all the technique is strongly represented in the Oseberg grave's rich collection of textiles. The colours are now faded and appear in different shades of brown and grey colour tones. Only the red colour has kept well and still has a fresh carmine colour. This colour appears so often it can appear as though it was the main colour.

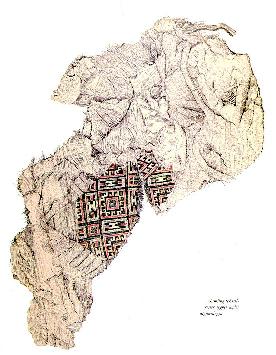

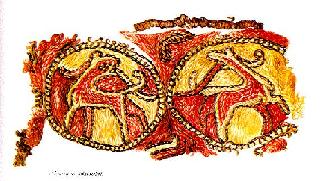

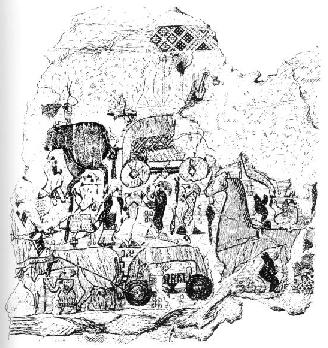

[The red colour has lasted better than the other colours, like here in the great wagon train. The tapestry fragment was sketched during the excavations.]

These narrow cloths seem to equal the Old Norse word 'refill'. Unlike a wide rug it was a long, narrow piece and of a more costly material than the rug. In modern terminology it's known as a [runner]revle.

Tapestries from Skog and Överhogdal in Sweden (Överhogdal C-14 dated to the 9th-12th centuries) can be considered commoner descendants of the refined tapestries manufactured at the court of the Oseberg queen. It has been suggested that the earlier examples of brocading in the braids from Evebø and Snartemo, which belong to the Migration Period, could be the origin of this art.

[Interior from the Oktorp farmhouse at Skansen in Stockholm. Photo: Skansen.]

Bjørn Hougen has placed the main emphasis on the stylistic analysis of these runners, but in another chapter of this book I will attempt to give a religious interpretation of them, since there can be no doubt that we here have mythological material of great value.

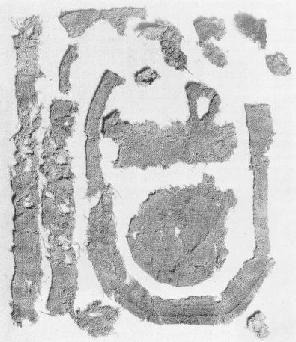

[Tapestry fragment from the Oseberg ship.]

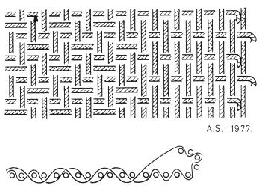

Another category of fabrics that has a lot in common with the runners as far as the weaving technique goes, is the tablet woven braids of which there are several. In these also the warp as well as the patterning is of wool, but it is clear that here also there must have been a double system of a vegetable fibre which has disappeared. By a lucky coincidence such a braid was found in the Oseberg ship with the whole warp with 52 tablets still attached. See ill. p. 187. Tabletweaving is a technique that can be traced far back in the prehistoric era.

[Illustration page 187. Tabletweaving as found in the grave.]

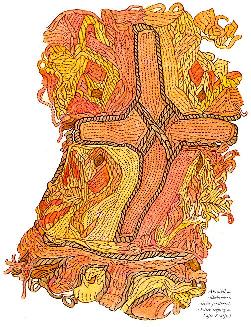

[Illustration page 177. Palmett, probably modelled after an Oriental silk.]

[Illustration Page 178. Collection of textile remains drawn during the excavations.]

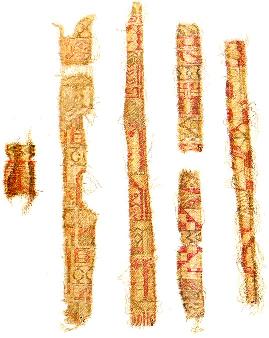

A collection of narrow silk strips exists. Some of them are shown here. See ill. p. 182. The fragments are currently under scientific treatment in Stockholm. For this reason it is difficult for me to say anything about the technical side to these textiles, since I haven't analysed them myself.

[Silk strips, cut up for application. Drawing by Sofie Kraft.]

It is possible that they all come from the same piece of fabric. The strips have needlemarks on both lenghtwise sides and have originally been attached to another fabric, probably of wool. There is reason to believe that this was one of the fine, probably imported two-shed and red fabrics mentioned below. Silk fabrics are found in no less than 50 graves at the Swedish market town Birka from the Viking age. They appear to be of the same origin as the Norwegian, and according to Agnes Geijer the majority of the Norwegian and Swedish silk fabrics appear to belong to the type known as 'samitum', which was manufactured in Byzantium and the Middle-East in that period. They were also cut up and found a similar use as decoration on plain-coloured pieces of clothing. One of the fragments from Oseberg has a pattern clear enough that it can be directly compared to a large silk fragment preserved in Lyon.

This group consists of 914 fragments. Some of them are in very bad condition and are now forming stiff cakes, often layered on top of each other. Others can be surprisingly well preserved. The material consists of remains of fabrics in tabby, several variations of twill or four-shed, slyngvev and soumakh, so-called slyngsmett. While I've been working on the scientific treatment of these textiles, I could not help but admire the women who, with their primitive tools have managed to produce textiles of such a high quality as these fragments show. I doubt that one today could, even with our modern advanced looms, make them any finer.

[Tapestry fragment with horses. Watercolour by Sofie Kraft.]

In connection with his work on older iron age textiles Bjørn Hougen once said: "It is possible that the technical tool, the loom, was fairly simple, but the end result can in no way be called primitive." The Viking age women had a long, unbroken tradition behind them as far as textile production is concerned. Here they had a wealth of experience handed on from mother to daughter through many generations. In our days this continuity of experience has been broken, and we are forced to again search for much of what to the olds was obvious. The old ones knew that to achieve a good result in the end product, everything had to be planned very carefully. From the very beginning it had to be decided what qualities one desired from the finished cloth. The textiles in the Oseberg find show clearly that everything was planned down to the minute details, and every stage in the preparation was decisive, not the least the quality of the wool which would be used.

[Fragment of woven braid. About double size. Water colour after drawing by Sofie Kraft.]

It is likely that we in Norway as early as the Bronze Age had a fully developed sheep industry, and that the sheep belonged to the short-tailed, goat-horned sheep breed Ovis aries palustris, which is related to our modern spel sheep. This breed had long, shiny kemps and a particularly fine undercoat, which was extraordinarily well suited for woven cloth. This sheep had the characteristic that it shed the wool in large clumps, which were easy to collect. Originally perhaps this was satisfactory. But from the Viking age graves we know large shears, which have been interpreted as sheep shears. There is therefore reason to believe that the wool of the Oseberg textiles was cut. This theory is supported by the fact that there is no roots on the wool fibres in the Oseberg material, and that a pair of shears were found in the grave, see ill. p. 185.

[Illustration Page 185. Shears from Oseberg.]

The spinning was done by spindle. In the Oseberg ship was found a functional whorl of clay shale with the spindle attached. There were also several loose spindles. With this primitive tool the loveliest, fine and even threads were spun. It could not be done better today with our advanced aids.

The whorl is one of the most commonly found tools in female graves of the Viking age. This shows that spinning must have been done by virtually every single woman in our country. However, some will have been better than others, and that it might also have been a specialist task is not out of the question.

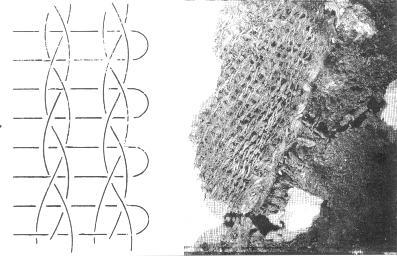

When the threads were spun, the warping of the loom could begin. Various circumstances make it clear that the Oseberg textiles must have been woven on a so-called warp-weighted loom, which simply put is an upright loom with hanging warp. At the bottom of the warp warp-weights of stone were attached to keep the warp threads under tension. The warp was created by weaving a narrow braid on a heddle or such, but the thread which was brought into the weave from one side, was brought out in a long loop or a warping frame on the other side before it returned to the weave again. A warp that is created thus will have a closed starting border on the finished cloth. See ill. on page 192 top.

[Illustration page 192 Top. Analysis of the starting border on a four-shed fabric. Drawing: Anne Stine Ingstad.]

A warp set up in this old fashion was found in a bog on the farm Tegle I Time on Jæren. It's been dated to the Migration Period. See ill. on page 192 bottom. This extraordinary and rare find is an illustration of how the Iron Age women set up their loom.

[Illustration page 192 Bottom. Warp with starting borders and warp weights. Found in a bog onTegle I Time on Jæren. From ca 500 A.D. Photo Norsk Folkemuseum.]

[Upright warp-weighted loom. Photo: Norsk Folkemuseum.]

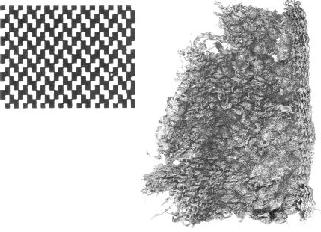

Two-shed is the simplest and oldest of the basic weaves. It is created by the weft going over one and under one thread of the warp each time. This group comprises 91 fragments. Most of them are fine with up to 27 threads per centimetre in the tightest system, which is probably the warp, and 14 in the other. The fragment with these measurements comes from a lovely red fabric, which is different from the other two-shed fabrics in that every other thread in one system (which it is can't be determined) is thicker and every other thread thinner. This must have been done on purpose, as it has given this fabric a beautiful muslin-like effect. The finest threads are 0.3 mm in both systems. The fabric was probably dyed with madder, as the colourant alizarin was found in it. This colourant also exists in a few plants that are native to Norway, but as fine as this fabric is, and as well as this dye has kept, there is reason to believe it is an imported fabric. The fragment is sewn together with another fragment of two-shed. This was also originally red, but it is now faded. Further, there is information that there was a small silk-fragment attached to the muslin-like fragment, but it has now disappeared.

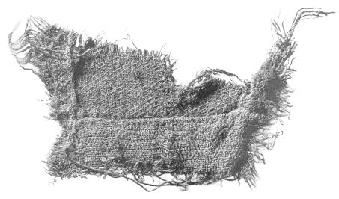

[Fragment of two-shed wool fabric. Oseberg.]

There are many fragments of the faded red fabric mentioned above. These are mostly cut up into narrow strips, of which one has an oval shape and might be a neck facing.

[Fabric strips of fine two-shed wool fabrics. Oseberg.]

Several of these fragments have fine, small embroideries that have been located along the edge of seams and applications. One fragment is sewn together with a silk fabric, of which a small piece is still attached. Here too there is small embroidery along the seam joining the two pieces. Some of the fine tabby, blue fabrics have been cut up for applications, which amongst other things portray animal figures.

The tabby fragments in the Oseberg material probably represents five or six different fabrics, of which three must be considered fine. Through the whole prehistoric period known as the Migration period (400-600 AD), tabby textiles are notable through their absence in the Nordic region, but in the years 700-800 they begin to appear again in the graves, particularly in the Western region. In Viking age they are abundant. There are several types of them. Apart from the two types mentioned already, there was also a third type, which has a ribbed effect. All these two-shed fabrics are right-spun in both systems and are characterised by their high quality. Outside the Nordic region these textiles don't have a wide distribution, but all three fabric-types appearing in our graves appear in Ireland during the Merovingian/Viking age. They are common along the whole Norwegian coast during these periods, and they often appear in the graves alongside articles of anglo/irish origin. In Ireland fabrics of the previously mentioned types with right-spun threadsystems are so to speak solely found. Fourshed fabrics are rare there. It could therefore appear as though this kind of fine, two-shed fabric was an Irish specialty. This is supported by the fact that it's particularly common in the Western Norwegian graves, and as mentioned along with anglo-irish articles.

Twill is another of the basic weaves. There are several types: the weft floating over two and under two warpthreads creates 2/2 twill or so-called diagonal twill. Because the entrypoint is moved one thread sideways each row, diagonal lines are created in the weave. There are many fragments of this type in the Oseberg material, both coarse and fine. The finest have between 14-28 threads per cm in the tightest system and between 8 and 20 in the other. Many fragments are in surprisingly good condition, almost as though they'd just been taken off the loom.

[Fragment of four-shed wool fabric with tubular selvedge. Oseberg.]

There are many selvedges preserved. They are tubular woven and can appear like a fine hem. The selvedges are created by first bring the weft right out to the edge, but instead of going straight into the shed on the return path a certain number of warpthreads were skipped, depending on how wide one wanted the selvedge. Then it was tensioned, so that the outer edge of the fabric was folded over and came to lie where the weft returned to the shed. The selvedges have some small differences, and so we know that these fragments must come from several pieces of cloth. There are so many pieces with selvedges in the material that it is likely that the cloth hasn't been cut, but rather used whole as blankets.

[Analysis of tubular selvedge on a four-shed wool fabric. Oseberg. Drawing: Anne Stine Ingstad.]

Several so-called starting borders are also preserved on these fragments. These borders are caused by the special way of setting up the warp, which is described on page 190.

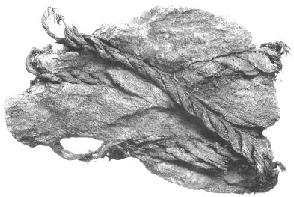

Some of the fragments in this group appear to come from the clothes the dead were buried in. There are some fine, blue fragments with seams, which appear to be from a gown. We will look closer at this in a later chapter. There were also several fragments coming from either a tent or the ship's sail, as there are a number of rope ends sticking out between the layers. See ill. lowest on page 197. All in all this group of the Oseberg material shows that 2/2-twill or diagonal twill was widely used.

[Illustration page 197 bottom. Wool fabric with rope ends. Tent or sail?]

[Analysis of wool fragment in cross twill. Drawing: Tone Strenger. Fragment of wool fabric in cross twill with tubular selvedge.]

Crosstwills are found in Norway in only two other Viking age finds, and it is not common in Europe either during that time. It appears as though this weave was particularly well suited for blankets that would have the nap raised. It is possible that these blankets can be identified as the so-called 'villosa', fulled cloaks produced in Mainz in the 9th century and exported to England. These could often be very fine, and were popular as gifts sent to prominent people. We know that Boniface sent such a villosa to the pope in Rome. It is also possible that our blankets are copies of these villosa, and that they were produced in the queen's workshop, something indicated by the selvedges. They are identical to the selvedges that appear on the diagonal twill fabrics, which are most likely woven locally. Tubular selvedges are only found once elsewhere in the Viking Age Norwegian material. Outside Norway there is one example in the material from Novgorod in Russia, and six from the Viking Age layers of Ladoga Staraja. There are also selvedges of this kind found in a couple of Polish finds from the 13-14th centuries. There is reason to believe that tubular selvedges are a Norwegian specialty of the Viking age, but that here also they were rare. Even stranger then that there are so many of them in the Oseberg material. Perhaps it is because this material must have contained so many blankets, which required a solid selvedge.

There are also five fragments of another fabric woven in cross twill in this material. It has a few more threads per cm in the respective thread systems, and the wool is very soft and fine. The fabric was probably originally white, but is now miscoloured by a red fabric that must have been lying in close contact with it. This is probably an imported fabric, as it has a very exclusive appearance.

[Fragment of rug in cross twill with sewn-on string.]

Diamond twill is twill which turns sharply in both warp and weft, forming a rhomboid pattern. There are three different groups with this patterning in the material. The finest fabric has 60-62 threads per cm in the finest system and 20 in the other. In other words there is a significant difference between the threadcounts in the respective systems. The finer the fabric is, the greater the difference. It is likely that the tightest of the systems is the warp. This particular fabric was made from red mohair. The fabric is very soft and shiny and reminiscent of silk.

[Illustration on page 200. Fragments of wool fabric in diamond twill. The fabric is made from mohair.]

Another fabric in this type of weave has 30 threads in the tighter system and 20 in the other. It somewhat more closed than the previous one, but was also originally red. The third fabric of this type has 20 threads per cm in both systems. It is significantly coarser than the other two and was originally dyed blue with woad. It is probably homemade. It has a preserved starting border, something that shows it was woven on a warp-weighted loom. There can on the other hand be little doubt that the other two fabrics were imported. Alizarin has been found in them, and they were probably dyed with madder.

[Analysis of the woolen fabric in the picture on page 200.]

The imported group of these textiles, which amongst other things is characterized by a large difference in threadcount in warp and weft, has a standardised appearance of on average a threadcount of 20/10, but a few other counts also exist. This notable standardisation has given scientists reason to believe that the textiles were produced in professional artisan environments somewhere abroad. The East has been suggested. All these diamond twill fabrics have right-spun yarn in both systems. The type has been given the name 'Birka type', as it appears in more than 40 graves in the Viking age trading town of Birka in Sweden. Another widespread group of diamond twill textiles has left-spun yarn in one system and right-spun yarn in the other.

The type that interests us here is the Birka type. The oldest examples of if are found in the Baltic areas - Bornholm, Skåne, Uppland and Gotland. The oldest are from the 7th century, the rest from the 8th. From this century we also know six norwegian finds, of which four come from Overhalla in Nord-Trøndelag, one from Sogn og Fjordane and one from Hordaland. In the Viking age these textiles become more widespread. In Sweden there's a strong concentration to Birka, in Norway they are particularly common in Trondelag and on the West Coast, and in the Viking age trading town of Kaupang (Skiringsal-Kaupangen) in Vestfold. Characteristic of this distribution is that they are found on or nearby places where there must have been trading, places that in the Middle Ages grew into market town or cities. As a rule the Birka type occurs in graves with a noble appearance, characterised by rich imported goods, rich jewellery, needle cases, and kitchen- and weaving implements. The male burials are often characterised by rich weaponry, and there are often smith's tools and scales. Further it is worth mentioning that the farms where these graves are found often have names ending in -vang, -heim or -stad, which further underlines that it is the most noble farms in the area we're talking about. They are centrally located, right by or near by places that grew into market towns in the Middle ages. This suggests that these places had a trading role already in the Viking age. Based on such associations I find it reasonable to believe that the textiles in question must have been traded.

Judging from the distribution of finds in Norway it appears that the oldest finds, such as the four from Overhalla in Nord-Trøndelag, must have entered this area from Sweden. In the century before the Viking age Overhalla was one of the most important entrypoints to Trøndelag for Swedish influences. In the Viking age the distribution of the finds is more even through the county, but it's strongly concentrated at the end of the dales which lead to Jämtland. Here the Storsjø area, which is considered to have been settled from central Sweden, may have been the trading centre which distributed goods from the Mälar area and Birka to Trøndelag, and vice versa. In the Vestland there is also a concentration of these diamond twill textiles at the end of the mountain passes, especially those with a connection to the various valley routes of the Gudbrand valley. This seems to suggest that these textiles were carried across the passes and down to the Vestland. When they appear to come through the Gudbrand valley, it is easy to believe they were carried the long way through central Sweden and into Norway where the Korsvinger track now enters. The journey continued across Solør and onto Mjøsa, then by boat across Mjøsa and up through the various routes through the Gudbrand valley and down to the Vestland. The only find of this type of textiles in the central country is from the lands of the Tråstad farm close to Kongsvinger. From very early times the Glomma ferry landed here. This textile fragment then seems to mark where these fabrics entered the eastern parts, Østlandet. When there are no other finds like it in the whole Østland area, this could be due to a different kind of burial practice that did not leave textile remains in the graves. There are many uncertainties here. The total lack of this type of find here has indeed been the main argument for these fine textiles being produced on the Vestland, since the most of them are found there. Some of them must undoubtedly have been woven as copies of imported textiles, but there is really little doubt that the finest of them were imported to Norway. It is probably Birka that was the transit point for these textiles. There is little likelihood they were produced in Sweden. Everything suggests they were originally from the East somewhere, where similar textiles much have been produced long before they began appearing in Nordic graves. There are extraordinarily fine diamond twills in graves in Palmyra in Syria and in Antinoë in Egypt that are from the 4th century. These are much finer than those found in our graves, but they all share the same characteristics with our textiles. That there is a connection here must be considered without a doubt.

Herringbone twill is another variant of twill. It is closely related to the diamond twill and is characterised by the regular turn of the diagonal in the direction of the warp or the weft, forming a 'fish-bone' pattern. This type is rarer in Norway than the previous, but since these are very small fragments it can often be difficult to tell the difference between herringbone twill and diamond twill. In the Oseberg material there is a fragment of this type which has 30 threads per cm in one and 14 in the other system. The threads are right-spun in both systems.

[Analysis of wool fragment in herringbone twill. Drawing: Tone Strenger.]

Slyngvev is the name of a weave where two or more warpthreads wind themselves around each other and are adjusted in the shed. In the Oseberg material there are some few wool fragments of this type. The fabric was probably originally white, but is now grey/beige. The type is related to the so-called 'Carelian lace' but I have not been able to find any good similes to our example. See Ill on the next page.

[Fragment of wool fabric in Slyngevev, and analysis of the same fabric. Drawing: Tone Strenger.]

Soumakh or 'Slyngesmett' is a technique that is relatively little known in the Nordic area. The weaving is done through winding a weft thread around each warpthread in a way similar to stockingstitch. They are then adjusted through the next row. A fabric produced in this way is similar to a tabby with a ribbed effect. It's known as Oriental Soumakh. In our material there are some rather small fragments of this technique. AS the warp threads in this case were of wool, it was possible to analyse the piece. In other instances the warp threads must have been made of a vegetable fibre, since there are now only remains of threadspirals left. People from the Caucasus and nearby areas used the technique in more recent times for fabrics that were subject to heavy wear and tear, such as saddle gear. This might mean that our fragment comes from an imported fabric, possibly a belt? But then it shouldn't be that hard to copy it either.

In the Oseberg find this type of fabric is now completely destroyed, but it is clear that they must once have comprised a large part of it. A few fabrics have been associated with down and has left black marks on feathers, for example one from a slyngvev, the mate of the one in wool discussed previously.

[Impression on down of a vegetable fibre fabric in slyngvev.]

Another fabric was a tabby. It had 9-10 threads per cm in both systems. The vegetable material in both these fabrics was linen, according to A. M. Rosenquist. Apart from the mentioned impressions some black cakes can be observed on other textiles. These are possibly the remains of deteriorated vegetable fabrics of linen or nettle. There was a flaxseed in a box in the fore of the ship along with some cress seed. This might suggest that flax was grown on the Oseberg queen's farm. It could also come from a flax plant that grew among the cress, since these two plants often appear together in the fields. But there is still much to suggest that flax may have been grown on the farm. Flax is an ancient cultivar, which must have been grown early on in Norway also, as is attested by placenames.

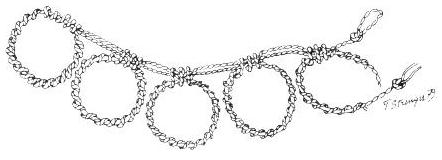

Embroideries occur on two-three fragments of the tabby, which once was red. They were quite tiny motifs executed in silk and wool or just wool. They appear to have been sewn on the edges of seams or appliqued silk- or wool fragment. The embroideries are executed in different techniques. They might be stemstitch and backstitch, in some cases they consist of several threads wrapped around each other. One small motif was found on the edge of a silk fabric. It represents five rings and are reminiscent of the 'olympic rings'.

[Analysis of embroidery. Drawing: Tone Strenger.]

The embroidery is done in two-ply woolen thread, and it was done by two threads, one forming the base or core for another thread wound around it. This type of small embroidery is known from the graves in Birka, and there too it is placed along the edges of seams and applications.

[Embroidery on wool. Oseberg.]

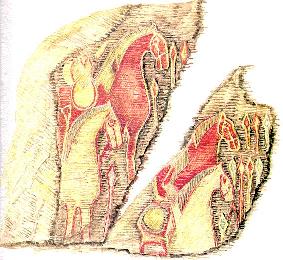

Embroidery of a different kind than the one mentioned above occurs on a silk strip. It can barely be seen through a crack in a textile cake. It has not been possible to undertake an analysis of the embroidery, but it could be a chain stitch that appears to have decorated the silk strip lengthwise. In a class of their own are two pretty embroideries done in silk. On one fragment there are two rings with an animal in each of them. Originally there were many rings in a row. Such ring patterns are known from the classical art where they often occur on silk fabrics. The embroidery is executed in different stitches with silk thread. See the illustration on page 179, top.

[Illustration page 179 top. Watercolour of silk embroidery.]

The other embroidery is probably a plant motif executed in silk thread, mostly in stemstitch that covers the entire surface. See ill on page 180, These embroideries are believed to be imported from the British Isles.

[Illustration page 180. Watercolour of silk embroidery. Much enlarged. After drawing by Sofie Kraft.]

Small seams occur in a few places, both as repairs of tears or on fragments of fabrics sewn together. Amongst others, two blue twills were each sewn together with a piece of diamond twill (see the picture above) in such a manner that one fabric overlays the other.

[Fragment of diamond twill and another twill sewn together.]

This suggests that the sewing abilities were not level with the weaving arts, as the stitches are clumsy and awkward. Finally some small applications in the blue tabby should be mentioned. Several of them represent animal figures, but they are also clumsily done.

There are two fragments of felted wool in the material. The pieces are no more than 2 mm thick, and it's doubtful if they can really be called felt. It is hard to imagine what these thin flakes could have been used for. It is possible that wool was worn in the shoes, and that due to heat and sweat the wool turned into felt. Otherwise it's hard to imagine what practical use they could have been.

One catalog number consists of four lumps and one small fragment of leather. The largest lump measures 9.5 x 1.5 cm. To one of them a thin string is attached which is made up of five right-spun wool threads. They are now dark brown. Inside the lump there is a small space, which hid a seed which through analysis was shown to be hemp, (Cannabis sativa). This was probably a pouch with seed in it, which one of the women wore around her neck, or it might have been placed somewhere on her body. There were also found four seeds of Cannabis sativa among the bedding. These could originally have come from this pouch.

Fulling is a kind of after-treatment of fabric. With a thistle or carder or some other tool a nap of loose fibre ends was raised on the surface of the fabric. This type of after treatment was done on the A-group of textiles in our material, the light blankets with tubular selvedges.

The finest of the tabbies were dyed after they were woven. This is easy to establish, as the colour is lighter where the threads cross each other, but also inside the threads. We don't know if it was common to dye whole pieces of cloth in the Nordic areas during the Viking age, or if we should see the examples of this technique in our material as an indication that these fabrics were imported. Since it is some of the finest fabrics in the whole material and additionally dyed red, the latter is likely. It appears as though red dye was an English speciality. In a market roll from St. Denis from the beginning of the 8th century it is mentioned that people came across the sea to buy wine, honey and madder.

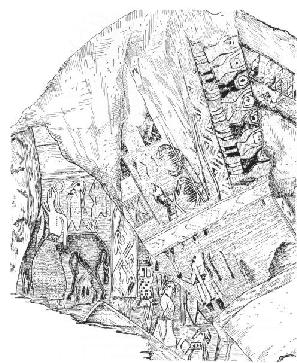

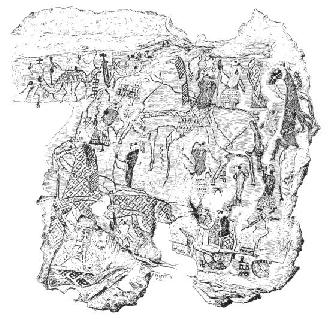

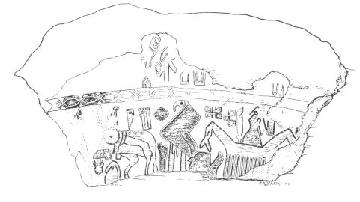

Female figure and horse. Drawn by Sofie Kraft.

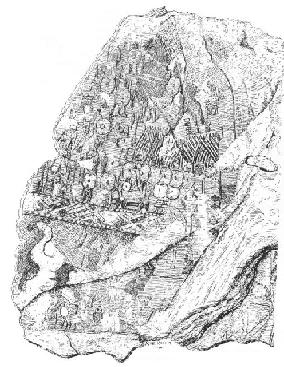

The wagon train. Drawn by Sofie Kraft.

The wagon train 2. Drawn by Sofie Kraft.

The sacred grove. Drawn by Sofie Kraft.

Battle scene. Drawn by Sofie Kraft.

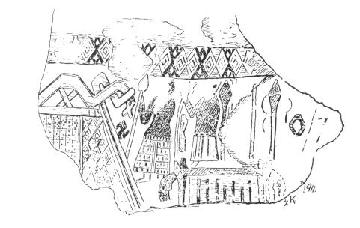

Horse and woman in the shape of a carrion bird in front of a house with dragons' heads on the gables. Drawn by Sofie Kraft.

Spear carriers outside two small houses with dragons' heads on the gables. Drawn by Sofie Kraft.

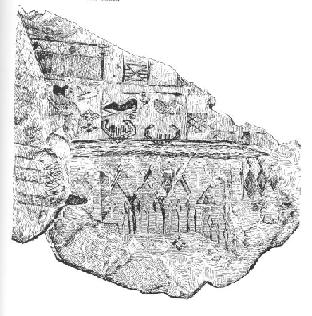

"Quay" with raised spears. A ship is drawing alongside. Drawn by Sofie Kraft.

Covered cart with dragons' heads. A woman walks in front of it. Drawn by Sofie Kraft